At a Glance

- Researchers showed how a ketogenic diet can enhance the effects of an experimental anti-cancer drug and starve pancreatic tumors in mice.

- The findings suggest that diet might be paired with drugs to block the growth of certain types of cancerous tumors.

Cancer cells need fuel to survive and thrive. The energy they need usually comes from glucose in the blood. Some studies have shown that intermittent fasting or a ketogenic diet—high in fat and low in carbohydrates—can help to protect against cancer. These cause the body to break down fat to form molecules called ketones, which can serve as the body’s main energy source while glucose is scarce. Fasting and ketogenic diets likely work by limiting the amount of glucose available to feed cancer cells. But some cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, can also use ketones as an energy source.

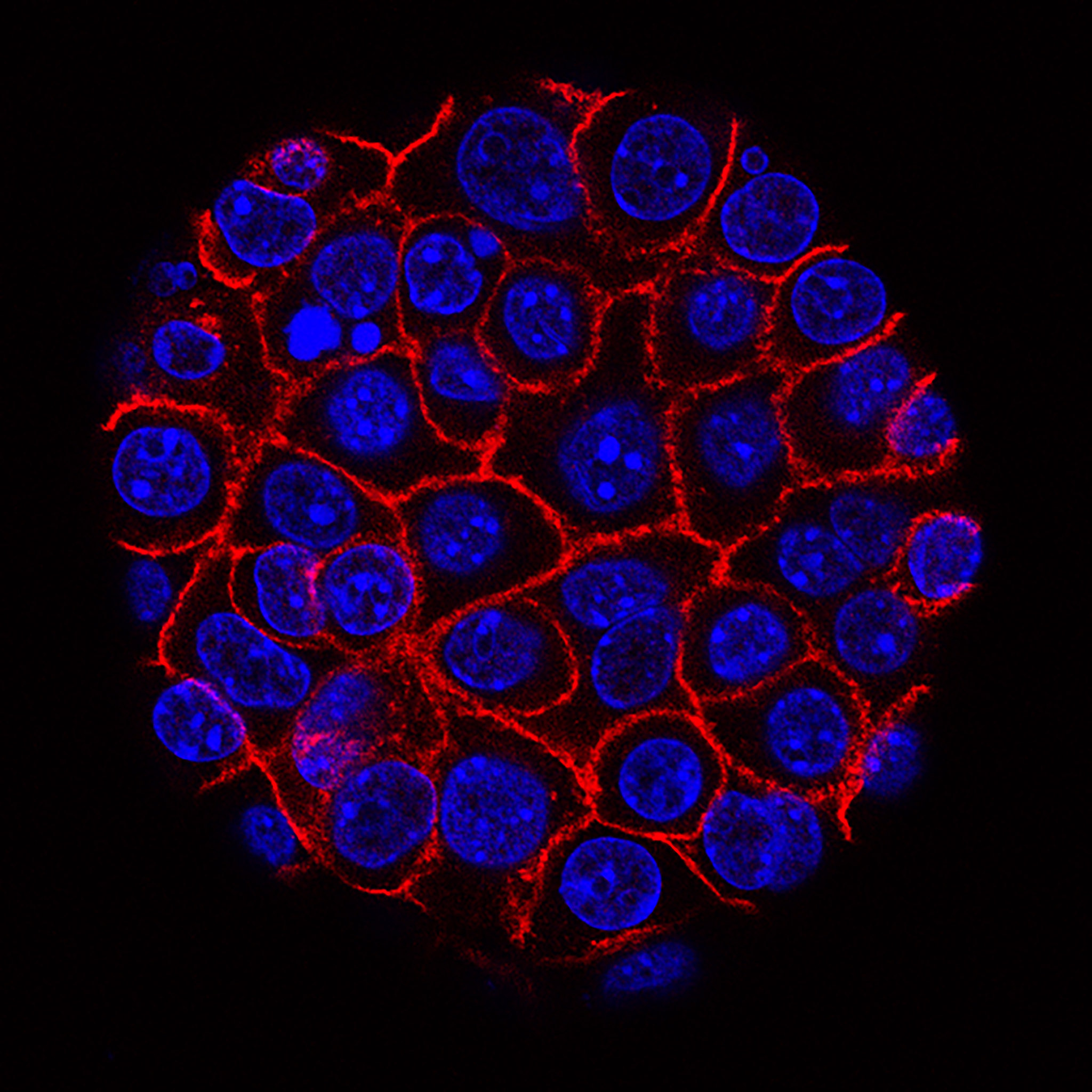

A research team led by Dr. Davide Ruggero of the University of California, San Francisco, set out to better understand the underlying gene activities and metabolic pathways affected by diet and fasting. They hope to use this knowledge to enhance cancer therapies. The team focused on a protein called eIF4E (eukaryotic translation initiation factor), which is often hijacked by cancer cells. Results appeared in Nature on August 14, 2024.

The researchers found that chemical tags called phosphates are added to eIF4E as mice transition from fed to fasting. Further analyses showed that this phosphorylated eIF4E (P-eIF4E) plays an important role in coordinating the activity of genes involved in processing fats for energy during fasting. When mice were placed on a ketogenic diet instead of fasting, the P-eIF4E protein similarly triggered a shift to using fat for energy.

The scientists next asked how fasting activated eIF4E. They found that free fatty acids, the small molecules released by fat shortly after fasting begins, activated a chain of events leading to eIF4E phosphorylation. This suggests that free fatty acids have a dual role, serving both as an energy source and as signaling molecules that boost fat-based energy production during fasting.

To assess the relevance of these findings to cancers that can thrive on fat, the researchers combined a ketogenic diet with an experimental anti-cancer drug that blocks P-eIF4E. The drug is called eFT508 (or tomivosertib). They found that giving eFT508 alone did not slow the growth of pancreatic tumors in mice, likely because the tumors could survive with energy from carbohydrates. But when mice were given the drug while on a ketogenic diet, the cancer cells no longer had ready access to glucose or fat for energy. The cells then starved, and growth declined.

“Our findings open a point of vulnerability that we can treat with a clinical inhibitor that we already know is safe in humans,” Ruggero says. “We now have firm evidence of one way in which diet might be used alongside pre-existing cancer therapies to precisely eliminate a cancer.”

—by Vicki Contie

References: Remodelling of the translatome controls diet and its impact on tumorigenesis. Yang H, Zingaro VA, Lincoff J, Tom H, Oikawa S, Oses-Prieto JA, Edmondson Q, Seiple I, Shah H, Kajimura S, Burlingame AL, Grabe M, Ruggero D. Nature. 2024 Aug 14. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-07781-7. Online ahead of print. PMID: 39143206.

Funding: NIH’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS); American Heart Association; American Cancer Society; Howard Hughes Medical Institute.